The Bear Den

AN EXCERPT FROM BLACK BEAR: A STORY OF SIBLINGHOOD AND SURVIVAL

In early November, snow drifted across the open fields. Grain stalks poked through the snow like beard stubble. I glided along the edge of the gravel road on cross- country skis, pushing forward, spearing my poles through the hard white crust, heading towards a long driveway that led past a stand of aspen to the old farmhouse. A truck pulled up behind me, idling. A woman was at the wheel, and she rolled down her window to talk to me.

“Do you ski often along this road?” she asked.

“Well, yeah, I live here.” I pointed one of my ski poles up the driveway towards the old farmhouse.

“Best be careful, because a few folks saw a black bear digging in the ditch last week,” said the man in the passenger seat. “It looked like the bear was digging a den.”

“Where exactly?” I asked.

“Just up ahead. There.” He pointed past the turnoff to my driveway.

I stared at the slanted, snow-covered earth between the road and a stand of aspen. It was hard to imagine there was a bear nestled into the side of the ditch. Why would a bear choose to den so close to vehicle traffic and the presence of people when, less than a kilometre away, the animal could dig into the valley slopes, prime denning habitat?

Only a small buffer of trees stood between the ditch where a bear might be denned and the farmhouse. Could it be the bear I saw in the grain field last month?

“I live here,” I said again, a bit dumbfounded. I’d heard stories of bears denning in culverts before, although they were rare.

“We just wanted to warn you,” the woman said before they drove off.

I nodded with a straight face, trying to hide my excitement. They obviously had no idea who they were talking to.

The next day, I took Holly and Skyla’s dog, Echo, to try to find the den. My boots crunched along the snow- packed road, while the dogs zigzagged in the ditch, following invisible scent trails. We walked to the edge of Skyla’s property line where the bush ended and an ocean of grain stalks began. Not a single tree stood in this section of land. Surely, I thought, a bear wouldn’t choose to den so close to a field of crops, without protection. I turned back, convinced that the people had been wrong; maybe the bear had actually been digging for roots, or chasing after a ground squirrel. Then I noticed Holly dip her snout into the snow at the edge of the road. She held it there for several long seconds the same way she would when hunting for mice who build tunnelled networks under the snow. If she had been hunting a mouse, she would’ve pounced with her two front paws and plunged her face deep into the snow. It was how coyotes and foxes hunted too. But Holly pulled back, as if alarmed, and retreated.

The den.

I gingerly touched my boot to the depression and the snow collapsed into a deep cavity. I gasped. I dared to nudge the edge again, and the hole widened into a gaping mouth.

The dogs circled cautiously, reaching with their noses, but wouldn’t step any closer. The people had been right: A bear was curled up right under my feet. I could see my bedroom window through the stand of aspen.

I stared dumbly into the den, uncertain what to do. I wondered whether I should alert conservation authorities, or a local biologist, or the municipality, who cleared the snow off the road every few days. Was the bear safe here?

I tied a piece of black cloth around an adjacent fence pole to mark the spot and headed back to the house, where I called a friend, a biologist who had worked on a black bear study in Colorado that used radio collar technology to track females in their dens. My friend would fold and worm his six- foot- tall body into the opening, holding a long jab pole tipped with a tranquilizer needle.

“They aren’t really sleeping, you know,” he told me. “They’re groggy and kind of looking around. Some are more awake than others.”

He and his team would tranquilize the bears, pull the mothers out from their dens, along with any cubs, measure their weight and size, and tag the cubs.

“Their dens give off this sweet smell,” he said. “Almost like honey.”

He wondered whether the bear’s choice to den in the ditch was actually an anti- predator strategy. Black bears, he said, sometimes prefer to den closer to human features on the landscape— roads, railways, houses, industrial sites— to use people as protection from other predatory species, including wolves and grizzly bears. It was true— grizzlies sometimes preyed on black bears. My father’s colleague had once watched a grizzly bear digging a black bear out of her den, shovelling heaps of dirt with his large front paws, to prey on her.

“Did you hear any breathing down below?” he asked.

“I didn’t get that close.”

“Sometimes you can actually hear them snoring,” he said.

I couldn’t stop thinking about my friend’s words. To listen to a sleeping bear— I couldn’t resist.

The following day, I went back to the den and quickly spied the ventilation hole, barely wider than the mouth of a coffee mug. Hoarfrost sparkled around its edges. I crouched and lowered my ear, holding my breath, listening for a heavy exhale. My heart drummed like a male ruffed grouse, louder and faster with every beat. Then a creaking sound from below broke the silence, as though the earth was moving. I fell backwards, found my legs again, and sprinted back to the house, sure that the sound was the bear, shifting, turning over in her den.

That night, I stared out my bedroom window. The snowy branches sparkled under the throw of moonlight. Somehow I felt comforted by knowing that the bear was there, so close, burrowed into the road. As I climbed beneath the covers of my duvet, I thought of the bear, curled in her den, and my loneliness softened.

***

When winter hooks its claws in the North, snow encases the earth, and bears curl into the warmth of their own bodies— hidden in old tree cavities, dug into slopes, protected beneath layers of soil and snow— and feed off their fat reserves. Bears ask their body to perform evolutionary magic. Their heartbeat slows to a rate of eight to ten beats per minute. They exhale once, maybe twice, in the span of a minute. They do not eat, drink, defecate, or urinate. Bears transform into large yogis beneath the earth, yet they don’t enter what’s considered “true hibernation.” Biologists refer to it as torpor. The animals rest. They wait. Their metabolism drops and they conserve and sustain their body’s energy resources to endure harsh conditions when food is scarce. Bears possess the ability to practise heterothermia— Greek hetero, “other,” and therme, “heat”— regulating their body temperature to match that of the surrounding environment.

Scientists believe that torpor may have allowed some mammalian species to survive mass extinction events. The oldest example of torpor has been found in the tusks of Lystrosaurus, a 250- million- year- old Antarctic animal that managed to survive the Great Dying, a massive global warming event triggered by volcanic eruptions that occurred 252 million years ago and decimated 96 percent of marine life and 70 percent of terrestrial species.

The black bear was imparting the most vital lesson for surviving a global pandemic: Hunker down through the discomfort. Wait it out.

***

Every day, I checked in on the den, observing, from afar, the ventilation hole. The dogs tentatively circled at a distance. I was envious of their ability to scent the bear. I imagined the honeyed aroma my friend spoke of. A part of me longed to crawl right in.

The size of the den hole varied with the unpredictable weather throughout December. As the temperature rose above zero, atypically warm for northern Canada, the snow cover melted, widening the mouth and exposing the surrounding dead grass. I wondered how the sudden thaw, a previously unusual occurrence in mid- winter that was becoming increasingly common in Canada’s northern boreal, would affect the bear’s cycle of dormancy. Would it shake her out of torpor?

Justin had recently told me a story about a local farmer discovering a black bear den along a road close to his property. The farmer lit a smouldering fire beside the den and fanned smoke into the opening to force the bear out. When the bear emerged, the man scared the bear onto his property and pulled the trigger. Perfectly legal. I worried about the same thing happening to my black bear neighbour.

I thought of the words of author and former superintendent of Banff National Park, Kevin Van Tighem, who’d previously told me that “black bears are like ‘second class citizens’ in Alberta.” They were the species of bear in North America that we seemed to treat with the greatest disrespect, and often, on the premise that their numbers were abundant.

Black bears, the oldest evolved species of bear on the continent, reproduce faster than grizzly bears and polar bears. They’re smaller, often perceived to be less threatening, and so commonplace they are often referred to by negation, that is, everything they are not. Not a grizzly bear. Not a polar bear. As the expression goes, “It’s just a black bear.”

In Alberta, it’s legal to bait black bears for the purpose of hunting them, or for employing the use of dogs, who chase and ‘tree’ the animals. Landowners can shoot as many black bears on their property as they want. There are no laws in place to protect black bears with the exception that it’s illegal to shoot a mother bear with cubs, or a juvenile bear younger than one-year-old.

***

One evening, Skyla spotted a black truck idling along the side of the road, close to the den hole. “I thought I should let you know,” she said. “Since you’re ‘the keeper of the den.’ ”

“Maybe it was just a coincidence he was parked there.”

“I don’t know. I kinda doubt it,” Skyla said with a shrug.

I knew she was right. There wasn’t any reason to park in that specific spot. Whoever was in the truck knew about the presence of the bear.

The next day, while driving to town to get groceries, I passed a green-and-white conservation truck heading back up the hill towards the farmhouse. A man in uniform was at the wheel. I whipped a U-turn and followed the truck, but the conservation officer didn’t turn down the road that led to the den. I pulled over, feeling sheepish. Once again, taking it too far. Organizing my life around a mystery beneath the earth. Skyla’s words echoed in my head: keeper of the den.

But I couldn’t stop caring about the nameless bear curled beneath the earth. I didn’t know how to go back to that mindset of “it’s just another black bear.”

***

In January, hoarfrost gripped the limbs of the willows by the bear den. Ice crystals clung to every living and non- living surface: branches, bark, fence post, even the electrical wires that slumped between the power poles. Even my exposed hair and eyelashes, as though I’d applied a thick coat of brilliant white mascara. The whole world had grown white, decadent fur.

I thought of the words of Cree, or Nêhiyawêwin, language consultant and knowledge keeper Jeff Wastesicoot, from Pimicikamak Cree Nation, whom I’d listened to recently as part of a webinar on Bear Teachings co- hosted by Indigenous Climate Action. “We tend to translate a little bit differently than what the English term knows about bear,” said Jeff. The Nêhiyawêwin word for bear is Maskwa, which is derived from the word for grass, Maskwaseek. In Nêhiyawêwin cosmology, bears are born from the grass. “[The English language] refers to it as a carnivore . . . and the word carnivore provokes fear. But the law of bear isn’t about fear,” said Jeff. “. . . It’s about respecting distances.”

According to Nêhiyawêwin beliefs, bears give birth to their cubs after the first hoarfrost in January. I stared down the ventilation hole laced with crystals and wondered if the bear was a female. Was she curled around two cubs, no bigger than a pair of shoes, groping blindly for their mother’s milk?

A friend had suggested I lower a GoPro into the den, but it felt, to my mind, like a violation of privacy. An invasion into the bear’s mysterious domain. I didn’t want to intrude upon the miraculous act her body was asking her to do.

Rest. Fast. Survive.

I’d never once see the bear, but all winter I dreamt of her, curled beneath the earth, cubs sliding forth from her body like a powerful river.

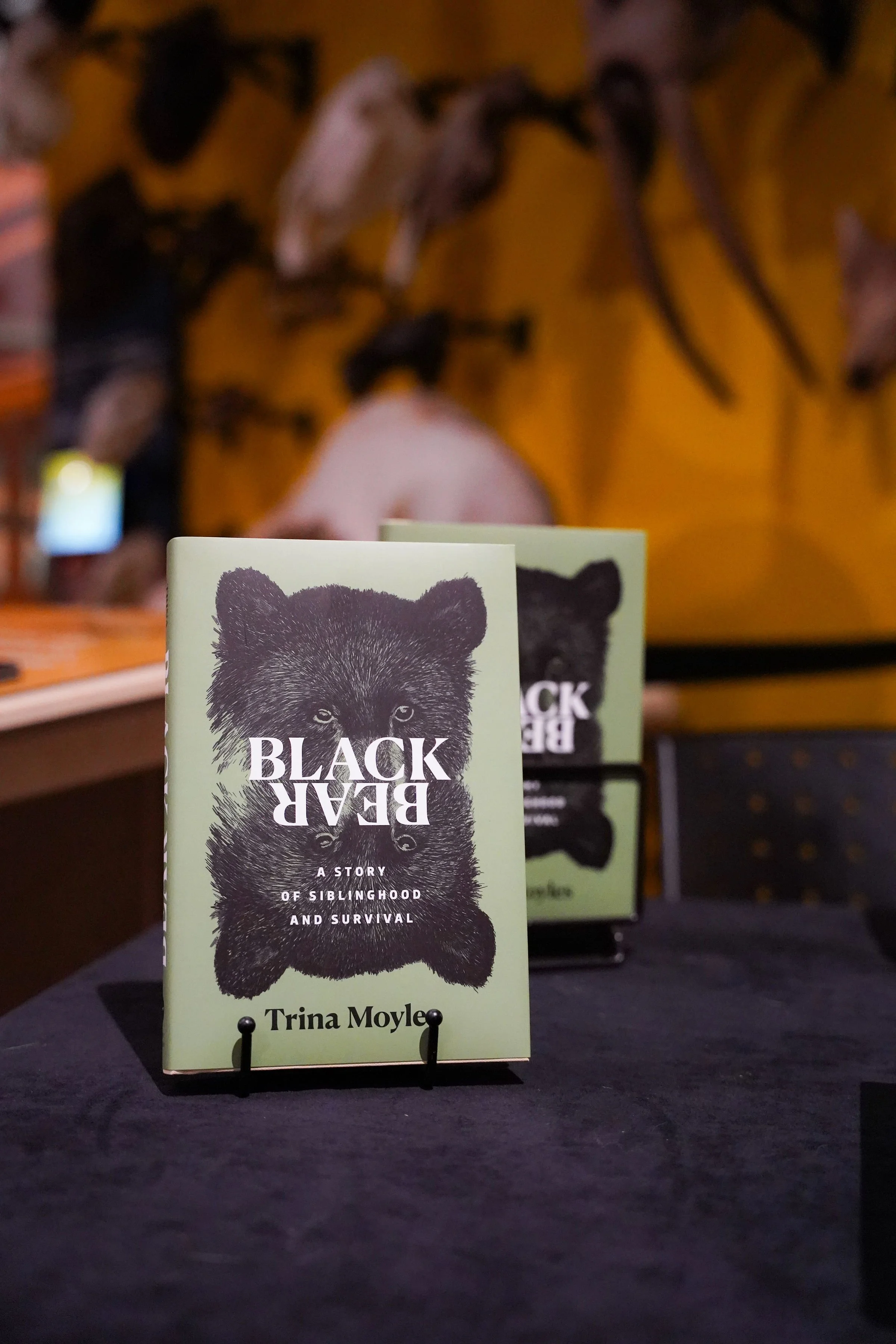

Excerpt from Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles (Knopf Canada, 2026).

Order Black Bear today

What a whirlwind of a week! Black Bear has already roamed far beyond any expectation I had of the book, with a sold-out event with Wordfest in Calgary and packed houses in Edmonton and Whitehorse—along with starred reviews in Publisher’s Weekly, Book Page, and Shelf Awareness, with a front of page feature in The Washington Post’s book section. This week it hit The Globe and Mail and Toronto Star’s bestseller lists, including bestseller lists in Edmonton and Calgary, too. Surreal.

I’m incredibly proud that Black Bear is being so closely observed by readers and featured in indie bookstores across North America. Thank you for reading and seeing the bears, so to speak.

REVIEWS

“It is a prodigious task to tell the story of two complex relationships…Moyles elegantly threads this needle by emphasizing subtly, yet persistently, the animality of humans and by gesturing to the common ground we, as siblings and parents and children, share with the bear familiar she observed in the wilderness.”

— Rachel Verona Cote, for The Washington Post

“Through keen observations and captivating storytelling, Moyles shows that survival is about finding inner peace and learning to overcome fears. This personal history goes straight to the heart.” — Publisher’s Weekly (starred review)

“Moyles is a precise, engaging, informative narrator who sweeps readers up in her vast world. The lessons that the bears teach her about herself, her brother and the value of human relationships are in turns heartwarming and heartbreaking. She seamlessly moves back and forth between natural and human habitats with elegant, understated prose, making her points with grace, logic and empathy. Black Bear is reminiscent of the very best nature writing, belonging on the shelf with Raising Hare, H is for Hawk, and Late Migrations.” — Alice Cary for Book Page (starred review)

Trina Moyles finds solace living with black bears in her new book — Edmonton Journal

Bear Watch: Trina Moyles writes about bears and siblings in new memoir — Calgary Herald

INTERVIEWS

CBC Radio Edmonton AM with Tara McCarthy

BOOK EXCERPTS

Bear defence and other survival lessons from northern Alberta — The Narwhal

“I heard the bear before I saw it” —Canadian Geographic

What a Standoff with a Black Bear Taught Me About Life in Northern Alberta — The Walrus

UPCOMING TOUR DATES

JANUARY 29 - OTTAWA - 7 PM

Can Geo Talks, hosted by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, 50 Sussex Drive.

FEBRUARY 3 - TORONTO - 7PM

In Conversation with author Claire Cameron, hosted by Flying Books, 784 College Street. Free admission.

A NORTHERN BC/AB & WEST COAST TOUR IS IN THE WORKS

…Smithers, Goodfare, Peace River, Vancouver, Victoria

Stay tuned…