The Forest Remembers

In Memory of legendary lookout DON ROSS (1951—2025)

I learned of Don’s passing on the same day a wildfire burned over the fire tower in late May. A former colleague sent me a photograph, taken from a helicopter the day after the flames devoured the site, leaving in their wake a pile of debris, the surrounding spruce forest reduced to ashes. Only the fire tower itself survived—the hundred-foot structure standing eerily sentinel, having witnessed it all.

The timing of the two events—the loss of the fire tower site and the loss of a man who’d committed decades of his life to watching from the fire tower—felt strangely connected. From my rookie season as a lookout, Don’s voice had always warned me about the possibility that a wildfire—fueled by drought, wind, and Mother Nature herself—could come out of nowhere and alter the landscape as we knew it. The fire responsible for the loss of the tower had taken a 30,000-hectare run overnight, my colleague told me. The surrounding forest was what firefighters refer to as “C2,” or “Boreal Spruce”—dense stands of black spruce, whose dead branches are often draped with pale green lichen, Usnea longissima, or “old man’s beard.”

When I was a kid, my dad taught me to pick a bundle of the flammable lichen to ignite our campfires. The lichen lived on the tree. The tree needed the lichen to lure wildfire up its branches and burst open her seeds. A symbiotic relationship.

That’s Mother Nature, Don would’ve texted me. We can only learn to go with the flow.

I accepted the loss of the tower site. The site would be cleaned. A cabin would be rebuilt. A future lookout would gaze out upon the charred forest again.

I was far less prepared to accept the news of Don’s passing. In March, he’d been diagnosed with a brain tumour. I’d reached out when I heard the news of his diagnosis. For nearly a decade, we’d corresponded through text—lookout to lookout—about news of weather, smokes, fires, flowers, and bears.

The last one was from January: a story about a memory of a mother grizzly bear and her two cubs who’d quietly wandered up to his cabin window. He’d been eating lunch at the kitchen table and was shocked to see them so close.

“A glass window will not stop a grizzly,” Don wrote. “I had no time for photos—time was perilous and precious—and even though I love to mingle with wildlife, I quickly shot off a bear banger right in that cabin.”

When I didn’t hear back from Don, I knew it must be serious, and I worried about my lookout friend. It felt akin to calling him over the two-way radio—“XMA685, are you by?”—and hearing only silence.

“I’m sorry,” texted my colleague. “I know you were close.”

That word, close. How do you explain to outsiders the family-like bonds that form between lookout colleagues, despite working entirely isolated from one another?

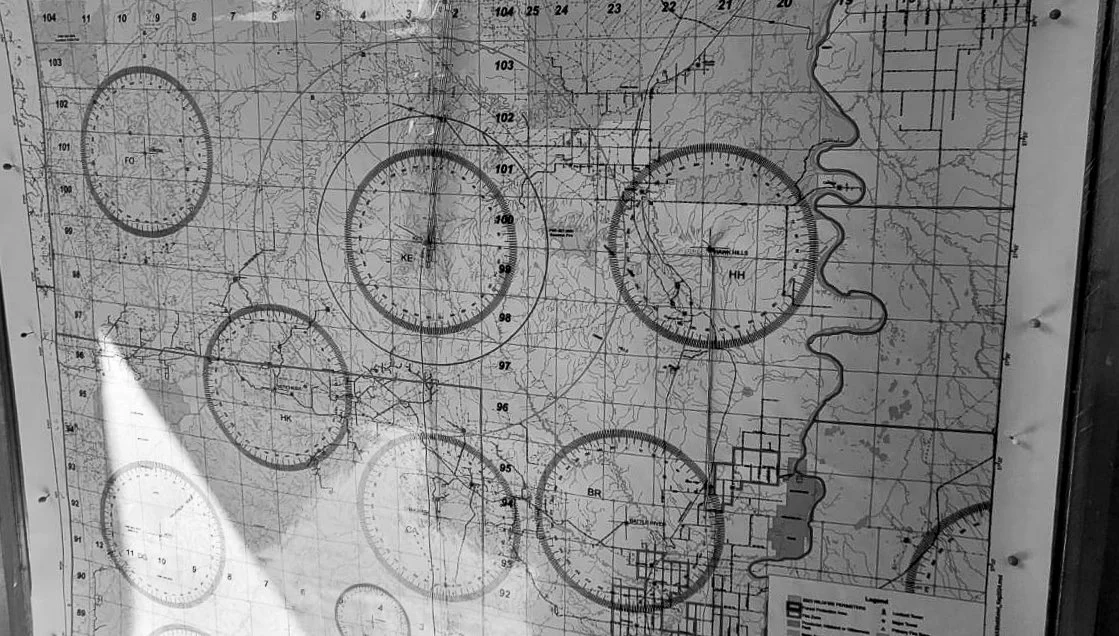

In my rookie season, Don and I manned towers that were built at nearly the same latitude, although fifty kilometres apart. I studied the cross-shot map of our respective towers—two circles indicating our ‘areas of responsibility,’ a 40-kilometre radius that overlapped slightly in the middle, like a Venn diagram.

When I looked east out my cupola window towards Don’s tower, a ridge rose up between us. I couldn’t see the forest on the other side. It was in my “blind area,” as lookouts say. If a wildfire sparked there, Don would see the column of rising smoke first—and vice versa on the west side of the ridge. It was in this way our relationship began.

On my fourth day on the job, a smoke appeared on the horizon north of our towers. The smoke was white as cotton and rose so furiously high into the sky that I froze solid in my cupola. I didn’t know I was looking at a grass fire, which can spread at a rate of twenty metres a minute. I also didn’t realize the wildfire had been caused by the screeching brakes of a train careening downhill, casting sparks into the cured grass. I was so terrified that I couldn’t do the very thing they’d hired me to do: pick up the radio and call in the smoke.

Fortunately, Don could see it, too.

“XMA26, this is XMA685 with a pre-smoke,” he said expertly over the radio, passing along information about the smoke’s colour, size, and location. He knew it was a grassfire burning along the rail tracks.

Minutes later, three additional smoke columns blossomed alongside the first, and the calm tone in Don’s voice gave way to the excitement he was widely known for.

“XMA26, there’s four smokes now!” he cried to the dispatcher.

“Thanks, Don. We’ve got it now. The Bird Dog is en route,” said Dar, a veteran radio dispatcher, gently assuring him in a motherly way.

Something I always loved about Don was that—no matter that he’d been working on towers for over two decades—he never seemed to lose the ability to be awed. Be it a smoke column, a sunset, a flower, or a mother moose with a calf, Don always seemed excited to bear witness.

I heard about Don and his lookout legacy before I was even flown out to my tower that rookie year. Based on what people told me about him, I was intrigued. He sounded like a true character—one of a kind.

Some of the stories seemed embellished, including one about Don’s habit of carrying a baseball bat around his yard to keep the bears at bay. (That would turn out, however, to be true. “You’ve got to remember the 3 B’s of bear safety, Trina,” he’d tell me. “Bear spray, bear banger, baseball bat. If they get too close, just bop ’em on the nose!”)

After the grassfires to our north had been quelled by crews, I called Don over the phone to introduce myself. That would be the first of many conversations over the seasons. Tower to tower, Don recounted memories from his twenty-some years as a lookout—and I listened avidly.

Born in 1951, Don had grown up on his family’s farm outside of Edmonton, Alberta. In 1980, Don signed up to work at Buffalo Tower in the High Level district. He struggled in that first season alone at the lookout. Buffalo was a busy tower; there were hundreds of active fire permits—which allowed landowners to legally burn brush piles—to keep track of, and that often got away. It would’ve, no doubt, been stressful. Don told me he suffered from homesickness in that first summer, keeping watch from up in the sky.

The young lookout was taken under the wing and tutelage of the legendary Sam Fomuk, the longest-standing lookout who worked on towers in Alberta from 1945 to 1994. Don moved over to Wadlin Tower, where he spent three years working closely with Sam, who manned the neighbouring Whitesands Tower. It was obvious that Don had been in awe of Sam, whom he described as being able to survive any kind of situation. In early April, Sam would be dropped off by helicopter with a big bag of rice, a rifle, and a fishing rod, Don told me. He’d shave his head at the start of the season, and when they picked him up in October, his white hair had grown in so thick that he looked like a dandelion gone to seed. Back in the ’60s and ’70s, Forestry allowed Sam to stay at the tower long after the risk of wildfire had waned, hunting moose and felling wood to feed the pot-belly stove in the cabin.

Don caught the tail end of that old lookout lifestyle, before the towers were outfitted with telephones and high-speed internet. He had to split wood and haul water from a nearby creek. (Today, there are no longer wood stoves—a fire risk. Cabins are heated by propane, and drinking water is brought in by truck or helicopter.) Like his hero Sam, Don developed an independent, maverick attitude, learning how to fix a busted two-way radio or venture outside the cupola—one hundred feet off the ground—to tighten the bolts on the steel tower.

He’d witnessed all kinds of unique weather, including “ball lightning”—something I’d never heard of before talking to Don. Ball lightning is described as a bright, glowing sphere of blue, orange, or red light, ranging from the size of a plum to a beach ball. Don told me that he’d witnessed the phenomenon during a particularly volatile storm: a strange and sudden orb of light outside his cabin. He went outside, and when the light moved toward him, he escaped back into the cabin.

Don had a special reverence for animals—domestic and wild alike. He told me a story of being no older than four or five years old and slipping into a paddock where a bull was kept.

The bull charged, but Don wasn’t afraid. Something in him told him that the bull wouldn’t harm him—and that turned out to be true. The bull stopped and sniffed his hand. He seemed to apply this same feeling toward the black bears that flowed by his tower every spring.

He often texted me with observations of the bears, punctuated with multiple exclamation marks. He referred to them as “Big Mama,” “Mr. Bear,” and the “tinies”—what he called the small cubs of the year that tumbled and frolicked on the slope. Don recorded detailed sightings and observations of different wildlife species, but especially of the bears. Tim Klein, a detection manager with Forestry, told me recently that Don’s end-of-season ‘Wildlife Sighting Report’—a document that had to be filled out by lookouts every season—“always read like a short novel.”

“Using words scribbled in the margins, on the back of each form, and on additional pieces of paper, Don would paint a picture of every bit of wildlife he either observed or heard throughout the summer,” Tim said.

Like most “lifers”—lookouts who migrate back to the perch every season—Don loved catching smokes. He was dutiful to his watch, climbing even on low-to-moderate hazard days. He seemed to prefer being up in the sky, observing the forest and scanning the horizon, rather than down on the ground. “Nothing’s happening today, Trina,” he’d tell me. “Boring.” His vigilance often paid off. Whenever I heard Don’s voice over the radio, I always jumped. Especially in my first two seasons, Don usually saw smokes before I did. I made many mistakes in those first years—calling in road dust, ghosts, pollen clouds, and other “false smokes”—but he was always encouraging. “Don’t hesitate, Trina. If you think you see something, call it in.”

In my second season, when I called in a black ribbon of smoke rising up from the ridge between our towers, Don swiftly jumped on the radio. “I’ve got a cross-shot on Trina’s smoke!” I smiled. I knew he’d meant it as a compliment. Trina’s smoke. Maybe he felt proud, too, because he’d trained me just as Sam had long ago trained him.

Don never stopped texting me during my seven seasons as a lookout, always sharing tips for how to spot smokes, live with bears, and survive the long seasons of isolation. Through the tower mail system, he sent me books and comic strips cut out from the newspaper, and poppy seeds from his garden.

After my third season, Don started saying, “This will be my last season, Trina. Next year, I’m hanging up my hat. I’m not coming back.” I quickly learned from my fellow colleagues that Don had been saying this for many years.

Every spring, I’d hear his voice over the radio again. He couldn’t seem to resist the urge—as though he was attuned to the magnetic draw north—to climb again. He didn’t need the money, Don told me. It was never about the money. Don just loved the act of witnessing, of being the first to see.

Like everyone else, Don had good days and bad days at the fire tower. We could all detect it in one another’s voices, as we read our morning or afternoon weather reports over the radio. A kind of edge would materialize in one’s tone, particularly mid-season, when the days on high hazard stacked up, or if your monthly grocery order had been delayed a couple of days due to rain, or fog, or—worse yet—another 310-caller had beat you to the punch, reporting a smoke before you could see it, which resulted in an unnecessarily bureaucratic “extra smoke” (which involved the duty officer calling you to determine why you didn’t see the fire first).

Don loathed extra smokes. If you really wanted to get the guy down, give him an extra smoke. “They shouldn’t even exist, Trina,” he’d rant. (Finally, I’m told, they no longer do.)

Sometimes Don seemed to play tricks on the radio dispatchers—particularly the newbies. He’d read his PM weather report like one of those wind-up toys: reading slowly, then speeding up to turbo speed, and you imagined the poor dispatcher on the other end of the radio call, typing frantically, trying to keep up to log his report. “Can you please say again?” they’d reply. I liked to call these quirks “Don-isms.” I listened avidly for them. I loved them. They always made me smile. I’m sure I had my own Trina-isms that I wasn’t conscious of. That’s what happens when you spend so many days and seasons on repeat, listening for the same familiar voices.

Don’s informality over the radio was what I loved most of all. He bucked against bureaucracy—not because he didn’t care about his job (he cared deeply, maybe obsessively, even)—but because he seemed intent on asserting his own unique self. On slow days, he’d jump on the radio and pass the radio dispatchers updates about the weather. “Alpha Charlie Charlie to the east,” he’d say, or “Thunder heard.” We weren’t really expected to give these updates, but Don gave them anyway. It built a sense of anticipation in the forest. Everyone was waiting for that first lightning strike and the first puff of smoke to crest the forest.

One afternoon, Don did call in a lightning-caused fire. He reported the smoke, which rose up then disappeared beneath a rain cell. Forestry dispatched a HAC crew in a helicopter to search for Don’s detection. They flew the bearing from his tower, but couldn’t find it.

“Don, where did you see the fire related to us now?” the leader asked over the radio.

“Oh, it was just at the base of those alien rays,” Don responded casually.

I burst out laughing, nearly choking on my coffee. I knew exactly what he was referring to—a beam of beautiful light emitted from the dark storm cloud, illuminating everything. It was the kind of informality that managers in Edmonton despised, but Don’s description worked. The crew found his smoke: a lightning-struck-one-tree-wonder.

“Catch ’em small,” the old lookout adage goes. Don caught nearly everything.

Although Don’s voice was one I’d recognize anywhere, I’d only seen him, face-to-face, a handful of times. Once, I closed his tower for the season in late September, and we hurriedly met on the helipad—the helicopter dropping me off and picking him up. With the blades of the helicopter churning, Don’s disheveled grey hair whipped about in the wind, and his blue, earnest eyes sparkled.

2024 would be Don’s final fire season. He finally didn’t come back to the tower. While I know the forest is lonely without him, I’m quite certain Don’s spirit is somewhere out there amongst the towering cumulonimbus, witnessing the first spark of a catalyzed tree burning from the inside out—or maybe ambling along the well-padded trails of the black bears.

Don Ross was as true a wildfire lookout as they come—a legend in his own right—and I am grateful to have known him and called him a mentor and dear friend.

—XMA567, out.

In loving memory of Don Gordon Ross, May 18, 1951—May 28, 2025. My deepest condolences to Don’s family, including his sister, Lorraine, who gave me permission to share these words and stories.

Post-Script:

After publishing this essay about Don, I received the following photographs of the fire tower site that was burnt over by a wildfire in late May. Communications staff flew out to the site to repair the power generation for the radio repeater (which survived the blaze). They were amazed by the intensity of greenery rising up out of the charred forest. “Although the tower infrastructure will take time to be rebuilt, the surrounding forest has started to grow back,” the note read.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider “buying me a coffee” to help support my work as a writer.